How did combat end for your Civil War ancestor?

For some it may have come when they were captured and sent to a prisoner of war camp, as happened with Francis M. Poore in the fall of 1864. For others away from the main fields of battle, the end came with an announcement that the war was over.

For 17-year-old William B. Poore, the end came with all the speed and fury that could be found in a Civil War battle.

By the end of March 1865, the outnumbered and worn down rebels around Petersburg probably knew they couldn’t stop an all-out Union assault. The decisive blow began late in the afternoon of April 1, 1865.

On the right of the rebel defensive line, 12 miles southwest of Petersburg, U.S. Major General Gouverneur Warren’s V Corps struck forcefully into C.S. Major General George E. Pickett’s Division at the strategic crossroads of Five Forks. By 7 p.m. the bluecoats had nearly destroyed the Confederate force.

Nightfall and a determined stand at Hatcher’s Run by General A. P. Hill’s Confederate Third Corps kept the federals from sweeping through the entire army. William and his comrades of Mahone’s Division were not part of Hill’s stand because they were on duty north of Petersburg.

Commanders awakened William and his comrades around 1 a.m. on April 2. They prepared for battle. The infantrymen carried only their weapons, canteens and cartridge boxes. By 3 a.m., William and his fellow Mississippians were on their way south to Petersburg.

C.S. General Nathaniel H. Harris remembered that as they approached the Cockade City “the deep, heavy and incessant roar of artillery and the sharp rattle of musketry announced a more than ordinary conflict” around the city. Yankee artillery had bombarded the Petersburg trenches all through the night.

About 5 a.m. massive formations of blue emerged out of a fog and overwhelmed the thinly spread rebel defenders. Union Major General Horatio G. Wright’s VI Corps smashed what remained of William’s comrades in Hill’s Third Corps, rolled up the rebel flanks and headed for the Southside Railroad. Hill himself fell dead, shot by a Yankee corporal he had cornered.

The responsibility of putting up some sort of defense now fell on Major General Cadmus Wilcox. What remained of the Army of Northern Virginia needed time to pull back from their scattered positions at Petersburg and Richmond.

Lee planned to unite them at Amelia Court House, about 35 miles west of Petersburg. From there he could head west and then drop down into south into North Carolina and link up with the forces of Joseph Johnston.

But Lee needed time to get his troops across the Appomattox and James rivers. He needed to keep the Yankees out of Petersburg until at least the night of April 2.

The Confederates had prepared an inner line of strong fortifications just in case the federals broke through the outer line. From this inner line, the rebels could hold off the federals until the rest of the army had crossed the rivers. But no troops yet manned these defenses. First Corps commander Lieutenant General James B. Longstreet hurried Major General Charles W. Field’s Division toward the inner trenches but they also needed time.

Once again the job of buying time against overwhelming enemy forces fell to William and his fellow Mississippians. When William and the other 400 men of Harris’ Brigade arrived near the Newman house on Boydton Plank Road about 10 a.m., Wilcox ordered them “to take position in front of the enemy and detain him as long as possible.”

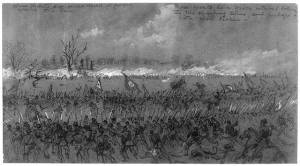

Finding the front of the enemy wasn’t hard. Everywhere William and his comrades looked, as far as they could see in front of them, an ocean of bluecoats floated across rolling hills. Individuals and groups of men from broken Confederate regiments fled eastward behind the Mississippians as fast their feet could take them.

The Mississippians had no time to watch their panicked comrades for long. In front of them the bluecoats closed in, their lines more than a mile long. The rising sun had burned off the morning fog and William and his comrades easily could see the bright sunlight glinting off Union bayonets.

“They seemed to be in no hurry, but very deliberately dressed their line and then moved forward,” one of the graycoats observed. “It was a grand, but awful sight, the federals moving with the same precision as though on parade.”

Harris knew he had no chance of stopping the large and powerful Union force, the XXIV Corps under Major General John Gibbon. But he believed he could slow them down and fool them into believing they faced a large force.

He did this by putting William and his comrades into a line so that the left end rested on Boydton Plank Road and stretched to the right toward the Appomattox River. They faced roughly southwest, at a right angle to the empty rebel trenches.

Harris put the ends of the line behind the crest of hills and exposed the center to Union view on the crest. This gave Union onlookers the impression of a long, continuous line of battle. The trick worked only until the firing began.

The brisk rebel musketry, backed up by two guns of the 1st Company of New Orleans’ Washington Artillery, proved too weak. Under orders from Wilcox “not to suffer himself to be cut off,” Harris had William, the other infantrymen and the gunners pulled back slowly to the east.

—NEXT POST: William and his Mississippi comrades make their last stand in Fort Gregg.

My ancestor, unfortunately, was wearing gray, not blue, so the end meant a long siege under poor conditions followed by surrender.

Kathleen, where was the siege and where did he surrender?

Gentry, John W. pvt., Grinstead’s 9th Regt. CSA: wounded and captured during the Battle of Arkansas Post, 11 JAN., 1863. Sent to the Yankee prison @ Camp Douglas, IL. He developed paralysis @ Camp Douglas, was paroled 3 April, 1863, delivered to City Point, VA and released. He was discharged 1 July, 1863 in Dinwiddie County, VA.

James, thanks for sharing. How well did John Gentry do after the Civil War? Did he recover from the paralysis?

My husband’s GG Grandfather John Glen Neal is buried at Franklin, Tn. He was wounded in the leg and died a few days later.

Sandra, what year did he die?